Project A-Ko has come to symbolize for me the type of anime popular in the west, just as anime started to become known here. I guess I've been around the anime scene for a long time, all things considered. I really got into things with Dragonball Z and got into stuff like Gundam Wing, Tenchi Muyo and Ranma 1/2 after that. Stuff like Inuyasha, Fullmetal Alchemist and Gurren Lagann still feel like they were relatively recent to me, but Gurren Lagann is over 15 years old at this point, and so is ancient by the standards of the generation of anime fans. I say all of this stuff not to brag or to complain about kids these days, but to establish how much of a relic of a bygone era Project A-Ko is. I had never heard of it when I got into anime, and even when I started looking at fansites after getting access to the internet, I only had a vague awareness of it.

However, due to a variety of factors, it's become clear to me recently that Project A-Ko was the big thing for anime fans slightly older than I am. I finally dove into it due to the well done bluray re-releases by Discotek. Since then I've been seeing Project A-Ko everywhere. It's a bit like when you buy a new car and you suddenly realize that the model and color of car that you drive seems to be everywhere, even though you never noticed it before.

Before all of this I vaguely recall seeing Project A-Ko being discussed on some old anime websites, and appearing on the recommended anime watchlist of Big Eyes Small Mouth 1st edtiion. (Incidentally that book, while not a very good RPG, serves as a fascinating snapshot of late 90's western otaku culture.) From this I would have been able to say that it was an OVA about high school girls, probably would have been able to identify A-Ko, and I knew that C-Ko was a brat. But that would be it. I imagine that people even five years younger than myself would know nothing about it.

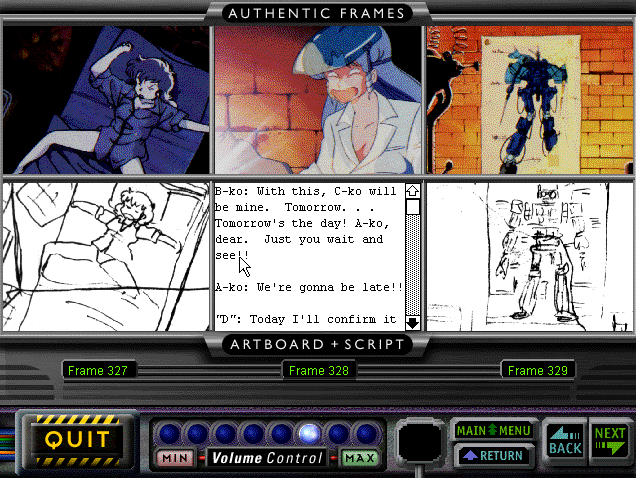

But after I watched the first Project A-Ko, I started coming across the show as I explored the past in a variety of ways. For example, as I said in this essay, while going through Windows 3.1 era software I encountered a program that played Project A-Ko music videos and had a screen saver. Since then, I have encountered a forgotten utility program themed around Project A-Ko. This is the "Project A-Ko Anime Hyperguide." The main feature of the program is to go through the movie, comparing frames of the movie to the storyboard, with the script included as appropriate.

It also has some clips from the dubbed version of the movie, a fanzine interview and concept art, and music from the movie. This was supposed to be the first in a series of other "hyperguides," but as far as I can tell no more were ever produced. You can see an archived version of the corresponding website here. It might as well be a Project A-Ko fansite, all things considered.

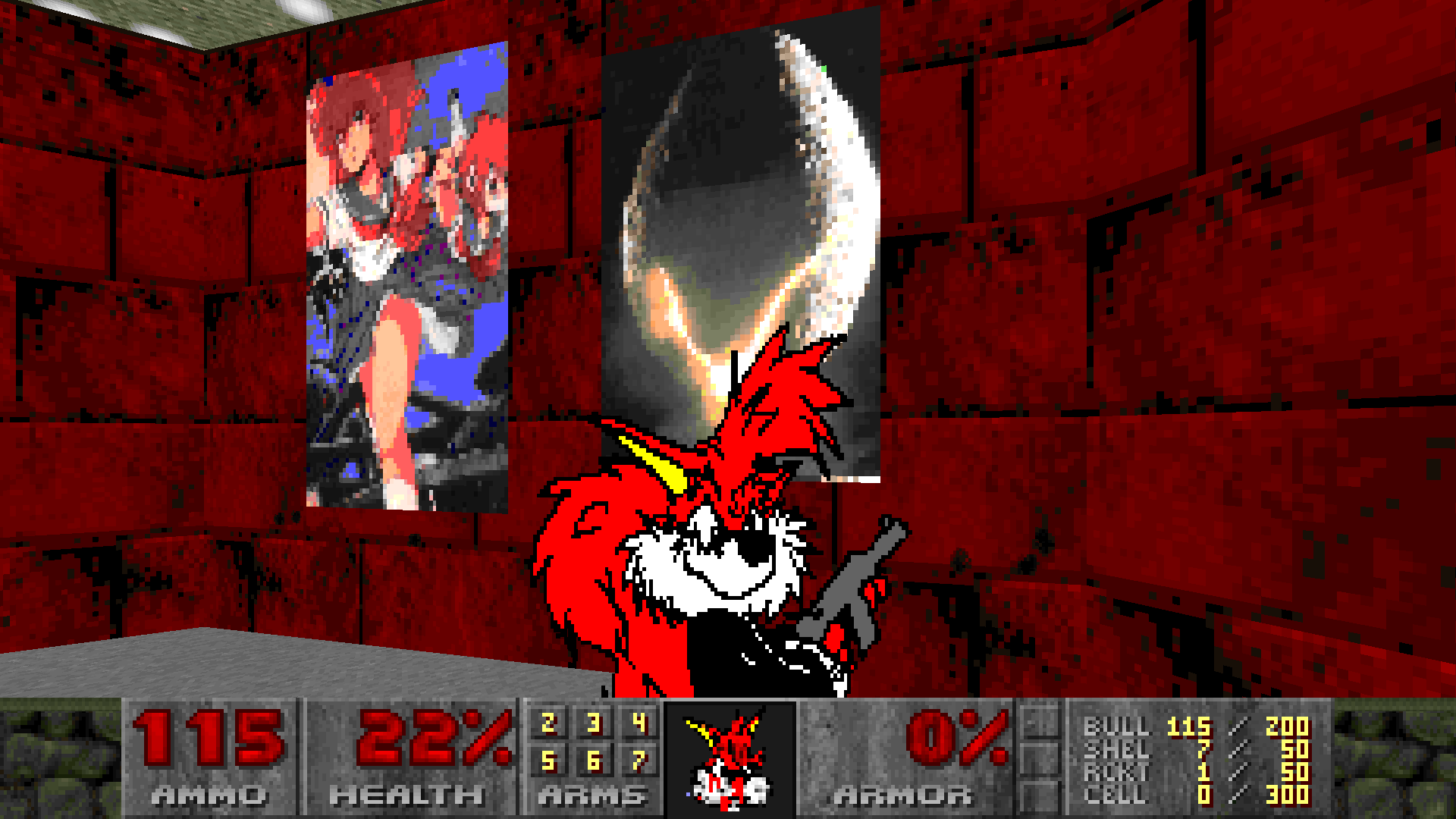

Now the hyperguide could be a fluke. Maybe Vanguard Media were mega fans, but the rest of the public wasn't (hence why there was only one hyperguide; not enough demand for the first one.) But then I started seeing the poster show up in old 90's DOOM wads:

(That's the somewhat infamous "Toons for Doom 2" by the way.) I think Ranma 1/2 shows up more often as an anime reference in DOOM wads, but I'm sure I've seen this pixelated version of the Project A-Ko posters on several occassions.

Project A-Ko is one of the only two anime referenced by the "Laws of Anime," specifically:

"#14 - Law of Inverse Lethal Magnitude The destructive potential of any object/organism is inversely proportional to its mass. First Corollary - Small and cute will always overcome big and ugly. Also known as the A-Ko phenomenon."

The other reference comes from a namedrop of Minmei, thus referencing Macross (or more likely, Robotech.)

But where things really started to click was in a recent visit to a thrift store. Some old school otaku had unloaded his collection. This included some old English anime fanzines. At the time I didn't pick them up, and they were gone when I came back later, so I don't remember the exact magazine, but I remember that Project A-Ko was referenced throughout, together with order forms for Project A-Ko 1-4 on VHS plus the versus OVAs. Really it's kind of insane at that point that there was a full run of anything anime, since anime was still pretty obscure (I think this magazine was from 1994 or so.) One was a December edition and came with Christmas post cards, featuring scenes from Ranma 1/2, Tenchi Muyo, Project A-Ko and Bubblegum Crisis. But what really surprised me was finding a run of Project A-Ko comics from Malibu. Not a translated manga, but something made in the US for the US fanbase. And then I came across a second Project A-Ko comic series (Project A-Ko vs. The Universe, which I think is based on the Versus OVA series, but it's hard to find any information about it.)

All this put together paints a picture of Project A-Ko being an absolute behemoth in the west during the mid to late nineties. Well, maybe "behemoth" is going a bit too far, as this 1997 snapshot of Yahoo shows that the number of Project A-Ko pages was dwarfed by the likes of Sailor Moon and Ranma 1/2, but certainly it was a well known anime in this time period. Then around the turn of the millennium, it became forgotten. I only have anecdotal information from this time period, though I do have some RPG/Anime trade order forms from that time that don't show anything from Project A-Ko. (It does have Galaxy Fraulein Yuna, another anime I keep running into, but that's a story for another time.)

In some ways I think this represents a change in how anime was received in the west. Why did I gain early exposure to the likes of Dragonball Z, Tenchi Muyo and Gundam Wing? Because they were on the Toonami block of Cartoon Network. Anime wasn't quite mainstream yet, but it was certainly readily available to those interested in it. You could go beyond what was on TV buy getting VHS tapes, and later DVDs, and certainly many people did this. But most people's viewing habits (including my own) were influenced primarily by what was on TV. In fact, in a way this is still how anime works. I know that most young fans do not really watch anime on TV, but this is because they don't really watch TV anymore. When they stream anime, they are just doing the modern equivalent of channel surfing. All this is different from the era where Project A-Ko came to the west. It was an era where anime was "readily available" in comparison to the previous fansub only era (and keep in mind this meant fansub on VHS, or perhaps "VHS with a printed English script for you to read.") Just buying able to go to a specialty form and buy an anime from a legit company, or to get a tape over mail order, was a huge increase of availability. But at the same time, it wasn't really something you could stumble into. It was something you had to actively pursue, right from day one. This may also be why references to Project A-Ko are common on old anime sites (even if they do not focus on Project A-Ko primarily.) In that culture fans must spread the word, as it were, to keep people involved. In contrast no fan really has to do anything to make sure that something like Attack on Titan or My Hero Academia is a success.

Another thing to consider is how weird and foreign Project A-Ko was during the time of it's top popularity in the west. Remember, its first official VHS relaease in the west was in 1991, and I'm sure that there were fansubs floating around before that. At that time, Japan's penetration of the US market was largely limited to Robotech, Voltron and some more obscure properties, together with some video games. The SNES had just been released, and even the likes of Dragonball Z or Sailor Moon were still not known. An American seeing Project A-Ko wouild do so from the perspective of it being a "cartoon," if maybe a foreign one. This is significant because Project A-Ko is an unabashed parody/homage to popular anime trends throughout the 80's. This included specific references, such as the teacher basically being an adult Creamy Mamy or the alien commander looking quite a bit like Captain Harlock and having the voice of Char Aznable. A lot of it was just in terms of general atmosphere, with the setting being a mash up of slice of life, magical girl (in the idol sense), mecha, post apocalypse, space opera shows and more. But a western viewer would catch hardly any of this. For a western viewer the result was just a concentrated dose of weirdness and over the top showmanship. This is surely why it was loved by its American fans: it represented a deep well of creativity that seemed unmatched by any other cartoon that they had seen. But at the same time this made it impossible for the show to become mainstream (and that's without getting into things like the frequent use of pantyshots.)

In contrast, now a lot of Japanese culture is simply American culture. When a new Final Fantasy game comes out, no one looks at it and thinks that the conventions and art styles used are bizarre and foreign. It's just another video game. Western cartoons like Teen Titans or Avatar: The Last Airbender stood out at the timne for openly aping anime conventions, but now these are over a decade old. Most young cartoon fans probably wouldn't even recognize that the art styles and gimmicks (like SD characters) even are something foreign, since so many other western cartoons since that point followed the lead of these shows. At the same time, shows like Dragonball Z, Pokemon, etc. are positively mainstream, and things like Cowboy Bebop or One Piece are pretty well known. If you dropped My Hero Academia into the early 90's, it would seem bizarre and full of new ideas, but at this point the main reason you know it isn't a western cartoon is the fact that the character designs aren't phoned in. It's a very different environment than the one that Project A-Ko thrived in.

I don't mean these observations to argue that the new or old anime fandom is superior. (I do have opinions on that, but they are largely unrelated to what I've been discussing.) What I am instead trying to convey is the fact that "the past is a foreign country." It's not just that Project A-Ko is less well known (and certainly not THE premiere anime anymore.) Rather, it is difficult for a new anime fan to even understand the context that Project A-Ko existed in. A new anime fan is likely to look back at Project A-Ko and dismiss it for being too generic (especially since many of the shots of the movie have been mimicked by later shows.) The idea that the movies would have been seen as bizarre and novel is not something that can easily be understood. Nor can be easy to consider that to be a Project A-Ko fan you would have to actively work at it, fighting to find each new tape and scouring books and sparse internet sites for more information when you couldn't get the real thing. Hell, I bet there were at least a few people who first "experienced" Project A-Ko by buying the previously mentioned Hyperguide and reading the script while flipping through the screenshots. And they would have thought that it was worth it, since that was the only way to experience this new and wondrous thing. It's not exactly Project A-Ko, and the reporting is cringey and unflattering as always, but here is a glimpse into the mindset. The die-hard Sailor Mercury fan in particular is notable, since he is often including second hand information about what happens in the show, despite obviously preferring to watch it. That simply wasn't an option, so he digs for what he can find.

In contrast, the new fan is able to easily watch far more series, and has no need to obssess about minutiae of later episodes. They can simply watch them. It is considered an unacceptable delay for a show to not receive an English translation in a few months, despite older fans searching for things for years. In such a world when a franchise did come over, more or less complete, it is easy to see how it would become so well liked among the subculture. And Project A-Ko in particular was something that was well suited to represent "anime" generally. Now there are hundreds of shows that can be watched at a moment's notice, even if you want to see only (legally) free shows. It's harder to get a crtical mass for a franchise without artificial hype. By that I mean that a corporation may decide to go all out on a show's advertising, merchandising, etc. and so make it "the next big thing." But it's more "top down" than the previous "bottom up" model of anime success (especially pre-Toonami.) The last thing that I can remember being primarily fan led was the interest in Kemono Friends. The attempts to archive the original defunct smart phone game did resemble the way people made anime shrines in the days of yore. But even that got ruined when Kadokawa caught on and tried to milk the franchse for all it was worth. It went from "work of love that shouldn't have succeeded, but was loved by fans" to "the thing that you need to buy figures and other merchandise for because the corporations decided you should." So in some sense Project A-Ko represents a sort of purity of the fandom which has long since been lost.

Originally I just wanted to chronicle my run-ins with random Project A-Ko related media, but this has turned into something a bit more rambling than intended. Maybe that's appropriate for an inaugural "anime category" article. (I've had the "anime" tag on this page for over a year, but outside of a few references to Gundam and Lain have done practically nothing with it until now.) There is a reason that why speak of "anime" when French cartoons and the like don't really have a special term for them, and that is the culture, which has shifted several times. Perhaps we will look at that in more detail down the road. But for the moment, it's probably better to leave things off here while this article is at least sort of coherent (if you squint at it.)

August 10, 2023